Published: tbd

Updated: July 24, 2024

When we speak about longevity from a health perspective we are speaking about more than just the length of time that someone is expected to live, also referred to as lifespan, but about the quality of time that someone is able to live without any debilitating issues such as chronic disease, cognitive decline, mental health challenges and physical impairment, which is referred to as healthspan.

Longevity, and the behavioral factors that contribute to it, can be a very complicated subject; however, I’m of the opinion it doesn’t have to be this way. Within all of the noise regarding the subject of longevity are basic tenets (i.e behavioral factors), and if practiced will contribute not only to increasing an individuals lifespan but also their healthspan.

Also it is best to keep in mind that there are no proofs, like there are in mathematics, when it comes to the subject of biology. The best you will get with biology is probability, the chance a certain event or result will occur, and when something is labeled as proven, it is simply meaning that all of the collected data shows that the probability of something being untrue is extremely unlikely.

The behavioral factors that are listed within the Basics fall into this category of proven. It is important to understand that within each behavioral factor you may find a myriad of information that is not proven, i.e. the research that has been done is inconclusive. As such I’ve chosen to avoid this information in this particular area of the website. That is not to say subjects like the geroprotective drug rapamycin are not covered on this website but to only point out that unproven factors are not discussed under the Basics website heading.

Behavioral factors are listed in rank order based on my research and what seems to be general consensus among the longevity community. The irony is that when it comes to the agreement around which behavioral factors are the most important, the community as a whole has a hard time agreeing on even the number of behavioral factors that should be included. One only need do a Google search for “longevity behavioral factors” and your results will return items stating there are (4) factors, (5) factors, (8) factors, well basically any number of behavioral factors related to longevity.

This guide deals with just the basics. It is designed to make the subject of longevity simple and straightforward so it is easy to put into practice. It is not meant to be an all encompassing list of every behavioral factor that impacts longevity, e.g. don’t become addicted to opioids. I think it goes without saying that opioid addiction can have a profound negative impact on longevity.

Behavioral Factors

Exercise

No single behavioral factor quite has the impact that exercise has shown for increasing longevity. The 2018 physical activity guidelines (PAG), 2nd edition, outline that for substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) to 300 minutes (5 hours) a week of moderate-intensity1, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity2 aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (JAMA). As lean mass (e.g. skeletal muscle) has also been shown to be an important longevity indicator (AM J MED), two of these exercise sessions should be committed to muscle strengthening exercises, i.e. resistance training. In addition, VO2 max is also considered to be another significant longevity indicator (FBL), thus aerobic activity, such as running, cycling, or swimming, should also be incorporated into the weekly workout sessions. Lastly, stability, like lean mass and VO2 max, declines as we age, so it is important that we also incorporate balance based exercise, e.g. yoga, tai chi, balance board, skateboarding, rope skipping, into our weekly regimen.

Strong evidence demonstrates that regular physical activity has health benefits for everyone, regardless of age, sex, race, ethnicity, or body size. Some benefits occur immediately, such as reduced feelings of anxiety, reduced blood pressure, and improved sleep, cognitive function, and insulin sensitivity. Other benefits, such as increased cardiorespiratory fitness, increased muscular strength, decreased depressive symptoms, and sustained reduction in blood pressure, accrue over months or years of physical activity (JAMA).

Sleep

It may come as a surprise for some of you that I have listed sleep as the second most significant behavioral factor regarding longevity; however, more and more evidence (MCP) is coming forward about the need for most individuals to get at least a minimum of 7 to 8 hours of sleep nightly.

Getting adequate sleep is crucial to the body’s function in that it allows us to restore and recover from our activity throughout the day. During sleep the body repairs cells, restores energy, and releases molecules like hormones and proteins; it removes toxins from the brain and helps write memories to long-term memory; and also plays a significant role in emotional well-being. This is only a small fraction of the activities accomplished while we are asleep.

Research suggests that regularly sleeping for less than seven hours a night can have negative effects on the cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, and nervous systems. Side effects of sleep deprivation can include obesity, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, anxiety, depression, alcohol abuse, stroke, and increased risk of developing some types of cancer (Verywell Health).

Sleep Suggestions

- Develop a routine that allows you to begin winding down for the evening and preparing for sleep. My routine includes setting my bedroom lighting to red @ 10% brightness (Sleep Foundation) and to begin cooling my room via air conditioning or open window down to 68 degrees Fahrenheit. I also like to read on my iPad before bed3(MNT) – Yes, you read that correctly.

- Make sure to have a consistent to-bed and wake-up time each and every day

- Keep your bedroom as dark as possible

- Don’t consume alcohol or caffeine beyond the early afternoon. Both can have significant impact on sleep quality in that they directly affect the phasing of sleep stages (NYT).

Nutrition

It may also come as a surprise that I have listed the behavioral factor of nutrition as the third most significant considering we have all been led to believe that diet and exercise are the keys to living a long and healthy life. And it is not by coincidence that the word diet is listed first in that phrasing, as pretty much since the mid-20th century it has been held that diet is the most critical component in determining the lifespan of humans. This is not to say that diet is not an important contributing behavioral factor in impacting longevity, it is, but to only point out that the importance of nutrition, related to longevity, over the last few decades has been overstated.

We also know that nutrition is unique to each individual based on genetics, age, metabolism, biological sex, and environment. Despite the slew of epidemiological studies on nutrition that have been done, the results of those studies are in most cases inconclusive for a myriad of reasons (Brown). What may work for one individual may have the exact opposite effect on another. Thus it is very hard to pin down specific nutrition practices that benefit the general population but there are some, e.g. minimizing ultra-processed foods (UPFs) reduces metabolic disease risk, and of these practices, there are those that show great promise for increasing longevity.

So although the subject of nutrition’s role and its impact on longevity is complex (and can be controversial), we can still point to specific nutritional behaviors that should be practiced.

Diet quality matters

The majority of your diet should consist of mostly whole foods; such as lean meats, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes, and minimally processed foods. Overly processed foods should be avoided as they are typically calorie dense, contain limited nutritional benefit, are less satiating, and have been shown to increase the risk of metabolic disease (Canhada), e.g. type 2 diabetes, heart disease, etc.

A 2017 study showed that participants who maintained a high-quality diet over a 12-year period, had a significantly lower risk of death from any cause (Sotos-Prieto).

Whereas in the past it was believed that minimal alcohol consumption was OK, and even reported to be beneficial to health and longevity, those studies have shown to be less than accurate in their findings based on a review of the methodologies used in the studies designs and interpretation of results (Zhao). Thus from a longevity perspective, no amount of alcohol appears to offer any health benefit, and may even increase all cause mortality, even when used in moderation.

Macronutrient Ratio and Protein

When it comes to macronutrients, i.e. protein, carbohydrate, and fat; and the ratio you should be consuming, it will be dependent upon the specific objectives you are trying to achieve such as gaining weight (under nourished), maintaining weight, losing weight (over nourished), and increasing/maintaining lean mass (e.g skeletal muscle), which we know decreases as we age and is critical to longevity.

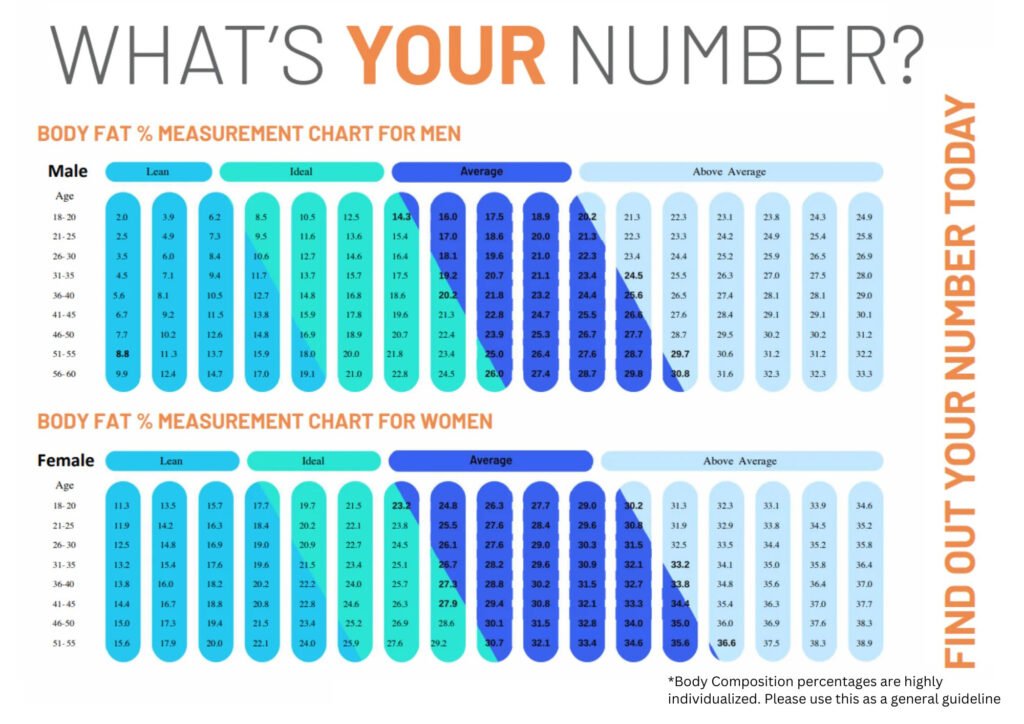

For example, I weigh 157 lbs at a height of 5′ 8″, with my most recent DEXA scan (performed 7/24/2024) putting my body fat percentage at 23.2%, which is in the ideal range (see nomogram below), and my fat free mass index (FFMI) at 18.97, which is considered average (Schutz). I am interested in maintaining my weight without losing any lean mass. My daily caloric target is 2,410 calories with a target macronutrient ratio of 50% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 20% protein.

Prior to my DEXA scan I was not really tracking my protein. Yes I was logging it but I was not paying too close attention to what this value was on a daily basis. After hearing that at minimum everyone should be consuming 1.6 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight in order to maintain lean mass, I decided to pay closer attention to this metric. Based on my current weight I should be consuming at minimum 114 grams of protein per day (71.21 Kg * 1.6 g = 113.94 g). Currently, I am consuming closer to 2 grams per kilogram of bodyweight as I clean up my diet, which entails consuming less alcohol on weekends and paring down the simple sugars.

The current understanding related to the amount of protein that can be synthesized by the body during any one meal ranges from between 20 grams (Schoenfeld) to 40 grams. General consensus has shown that older adults, due to anabolic resistance as we age, need to be towards the higher end of this range. Because protein, unlike carbohydrate or fat, are not stored by the body, any excess amount that is not used by the body is excreted as urea.

I want to make one last point on the subject of protein perfectly clear. Many of you reading this guide will pause when you see me state that “at minimum all adults should be consuming 1.6 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight”. Especially considering that the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) states half that amount for the adult general population (0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight). And there was a time where it was believed the RDA recommendation was sufficient; however, current research shows these numbers to be insufficient for the adult general population (Phillips).

Although it is possible to consume too much protein, the amounts listed in this guide when consumed by a healthy, adult, general population, should cause no concerns of an increased risk to health.

Having significant enough protein in your diet is important for either building or maintaining lean mass. As has been stated throughout this guide, lean mass, especially skeletal muscle, decreases as we age and has been shown to be critical to longevity, i.e it is one of the key longevity metrics. Thus monitoring your protein intake is a metric for which you will want to pay attention.

Calorie Restriction vs. Calorie Control

By now you’ve seen numerous articles and publications touting that calorie restriction has the potential to increase human lifespan, and a recent study, called the CALERIE trial, shows some promise (Waziry). However, there is still more research that needs to be done, e.g. longer randomized controlled trials, in order to come to the conclusion that calorie restriction can indeed extend human lifespan (Attia1).

With calorie control, we are looking to maintain, or establish, a healthy body weight that is appropriate for an individuals height, supports optimal physical function, and reduces the risk of chronic disease. This is done by establishing the total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) needed to maintain current weight. From this metric, we can adjust the daily calories, as well as the macronutrient ratio, based on whether the individual is either under nourished (needing to gain weight) or over nourished (needing to lose weight). Consideration should also be given as to whether they have the appropriate amount of lean mass based on their weight and height, which can be accomplished using various methods, the easiest of which, but not the most accurate, is a body composition scale.

To determine an individuals total daily energy expenditure we must first calculate their resting energy expenditure (REE). As we are looking to address the general population, we will use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation to calculate REE.

- For Men

- REE = (10 x weight in kg) + (6.25 x height in cm) – (5 x age in years) + 5

- For Women

- REE = (10 x weight in kg) + (6.25 x height in cm) – (5 x age in years) – 161

Using the formula above and myself as a reference, biological male, 71kg, 173cm, age 57, here is an example of the calculation:

- Calculation

- REE = (10 x 71kg) + (6.25 x 173cm) – (5 x 57) + 5

- REE = (710) + (1081.25) – (285) + 5

- REE = (1,791.25) – (285) + 5

- REE = 1,506.25 + 5

- REE = 1,511.25

Now that we have determined resting energy expenditure, we can calculate total daily energy expenditure based on the table below.

| Sedentary (little or no exercise) | TDEE = REE x 1.2 |

| Lightly Active (light exercise or sports 1-3 days a week) | TDEE = REE x 1.375 |

| Moderately Active (moderate exercise or sports 3-5 days a week) | TDEE = REE x 1.55 |

| Very Active (hard exercise or sports 6-7 days a week) | TDEE = REE x 1.725 |

| Super Active (very hard exercise or a physical job) | TDEE = REE x 1.9 |

I would consider myself moderately active, thus I would take my REE of 1,511.25 x 1.55 to calculate my total daily energy expenditure to be 2,342 calories. This works out to be about 3% lower (68 calories difference) than what the MyFitnessPal app has me calculated for daily calorie expenditure (2,410 calories) to maintain my current weight.

Maintaining a healthy body weight has been shown to lower the risk of all-cause mortality related to chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease (e.g. heart attack, stroke, etc.), cancer, and metabolic syndrome (e.g. type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, etc.), thus its importance to longevity cannot be overstated.

Glucose Control

The control of blood sugar, i.e. blood glucose, and it’s relationship to longevity, especially for those without diabetes, has become better understood as we have progressed through the 21st century. Studies have shown that individuals who are considered to have normal blood glucose levels by clinical standards, i.e. a fasting blood glucose level < 100 mg/dL, may still be at risk for metabolic issues caused by post-prandial hyperglycemia (PPHG), i.e. glucose spikes that exceed 140 mg/dL within two hours after the start of a meal4, that can impact satiety, mental health, sleep and present a greater mortality risk related to cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome (Jarvis).

Studies in individuals without diabetes have also shown that recurrent, large glucose excursions, such as those that occur in PPHG, may lead to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. PPHG has been shown to contribute to endothelial dysfunction (the thin layer of cells lining the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels), inflammatory reactions, and oxidative stress, all of which are closely associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality.

As such, we must take steps with our diet, and lifestyle, to mitigate the risks and reduce the incidence of PPHG.

In addition, it is important to have a way to measure if these diet and lifestyle changes are actually reducing the occurrence of PPHG. One of the best, and most informed ways to do this is through the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), where a small device is placed on the back of the arm that takes glucose readings from interstitial fluid in the body 24/7. These readings are automatically taken about every 5 to 15 minutes (dependent upon brand/model of CGM used) and are typically associated with an app that is installed on a smartphone to provide the user with their current glucose level and a trend graph to give the user an idea of how stable their blood glucose is over a set period of time. Only recently have CGMs become available without prescription and when combined with a manual blood glucose meter can prove invaluable in providing insight into an individuals blood glucose levels.

Even if you choose to not use a CGM, or a blood glucose meter, to monitor your blood sugar, there are still steps that you can take to control your blood glucose.

- Eliminate processed foods, but more importantly ultra-processed foods (UPFs), which provide minimal nutritional value and are high in sugar and sodium.

- Eliminate added sugars from your diet, which not only contribute to excess calories with minimal nutritional value but also have been linked to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. In 2016, the FDA updated the Nutrition Facts label on food to require that added sugars be broken out (fda).

- Increase intake of both soluble and non-soluble fiber to aid in slowing the absorption of sugar during digestion, thus minimizing glucose spikes after meals.

- Incorporate some low impact movement after meals, e.g. a 20-minute walk, to promote glucose uptake by the muscles and enhances insulin sensitivity, which can be particularly beneficial for those looking to maintain steady blood sugar levels.

Today, it is well-established that maintaining healthy blood glucose levels is crucial for longevity. Consistent glucose control can help prevent not only diabetes-related complications but also conditions like cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, which are major contributors to early mortality.

More recent studies have shown that elevated blood glucose levels, even those in the prediabetic range, are linked to increased mortality and reduced longevity. Large-scale studies and meta-analyses have found that people with consistently high blood sugar have a higher risk of all-cause mortality, due to increased risk of conditions like heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease (Cai).

It is important to take notice of the association between blood glucose and the other longevity behavioral factors, i.e. sleep, nutrition, exercise, and mental health, that are cited in this guide. Because of these interconnections, any effective longevity plan should include strategies for maintaining healthy glucose levels.

Mental Health

Social Connectedness

Longevity Metrics

Notes

1Moderate exercise intensity is defined as heart rate between 65% – 75% of your maximum heart rate (HRmax) [American College of Sports Medicine – 2020]

2Vigorous exercise intensity is defined as a heart rate between 76% – 96% of your maximum heart rate (HRmax) [American College of Sports Medicine – 2020]

3For me I find that reading helps me to relax and prepare for sleep and doing this on a screen seems to have no effect on me falling asleep. I do set my iPad to Apple’s Night Shift setting based on the original reports about light closer to the blue spectrum upsetting the circadian rhythm cycle. Latest reporting from Medical News Today regarding a study published in Nature Human Behaviour would seem to refute the previous research.

4According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), postprandial hyperglycemia is diagnosed when blood glucose levels exceed 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) within two hours after the start of a meal.

Works Cited

Katrina L. Piercy, PhD, RD, Richard P. Troiano, PhD, Rachel M. Ballard, MD, MPH, Susan A. Carlson, PhD, MPH, Janet E. Fulton, PhD, Deborah A. Galuska, PhD, MPH, Stephanie M. George, PhD, MPH, and Richard D. Olson, MD, MPH; “The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans” Journal of the American Medical Association JAMA. 2018 Nov 20; 320(19): 2020-2028. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9582631/ Accessed July 22, 2024

Preethi Srikanthan, M.D., M.S. and Arun S. Karlamangla, M.D., Ph.D; “Muscle Mass Index as a Predictor of Longevity in Older Adults” American Journal of Medicine Am J Med. 2014 Jun; 127(6): 547-553. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4035379/ Accessed July 22, 2024

Barbara Strasser, Martin Burtscher; “Survival of the fittest: VO2max, a key predictor of longevity?”. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) FBL. 2018, 23(8), 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.2741/4657 Accessed July 22, 2024

Virend Somers, MD, PHD. “Sleep and Longevity: How Quality Sleep Impacts Your Lifespan” Mayo Clinic Press MCP 2024 Jan 19. https://mcpress.mayoclinic.org/healthy-aging/how-quality-sleep-impacts-your-lifespan/ Accessed July 23, 2024

Mark Stibich, PhD. “The Relationship Between Sleep and Life Expectancy” Verywell Health 2023 Jul 12. https://www.verywellhealth.com/sleep-duration-and-longevity-2224291 Accessed July 23, 2024

Jay Summer, Pranshu Adavadkar, MD; “What Color Light Helps You Sleep?” Sleep Foundation 2023 Sep 13. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/bedroom-environment/what-color-light-helps-you-sleep Accessed July 23, 2024

Corrie Pec “Blue Light May Not Affect Your Sleep-Wake Cycle, Study Finds” Medical News Today MNT. 2024 Jan 5. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/blue-light-may-not-affect-sleep-wake-cycle Accessed July 23, 2024

Ameila Nierenberg. “Why Does Alcohol Mess with My Sleep” New York Times NYT. 2022 Jan 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/25/well/mind/alcohol-drinking-sleep.html Accessed July 23, 2024

Brown, Andrew W et al. “Toward more rigorous and informative nutritional epidemiology: The rational space between dismissal and defense of the status quo.” Critical reviews in food science and nutrition vol. 63,18 (2023): 3150-3167. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9023609/ Accessed September 3, 2024

Canhada, Scheine Leite et al. “Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Increased Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in Adults: The ELSA-Brasil.” Diabetes care vol. 46,2 (2023): 369-376. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9887627/ Accessed September 3, 2024

Sotos-Prieto, Mercedes et al. “Association of Changes in Diet Quality with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality.” The New England journal of medicine vol. 377,2 (2017): 143-153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5589446/ Accessed September 23, 2024

Zhao J, Stockwell T, Naimi T, Churchill S, Clay J, Sherk A. Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e236185. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2802963 Accessed September 13, 2024

Schutz, Y., Kyle, U. & Pichard, C. “Fat-free mass index and fat mass index percentiles in Caucasians aged 18–98 Y”. International Journal of Obesity 26, 953–960 (2002). https://www.nature.com/articles/0802037 Accessed September 6, 2024

Schoenfeld, Brad Jon, and Alan Albert Aragon. “How much protein can the body use in a single meal for muscle-building? Implications for daily protein distribution”. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition vol. 15 10. 27 Feb. 2018. How much protein can the body use in a single meal for muscle-building? Implications for daily protein distribution – PMC (nih.gov) Accessed September 13, 2024

Phillips, Stuart M. “Current Concepts and Unresolved Questions in Dietary Protein Requirements and Supplements in Adults.” Frontiers in nutrition vol. 4 13. 8 May. 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5420553/ Accessed September 9, 2024

Waziry, R., Ryan, C.P., Corcoran, D.L. et al. “Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial”. Nature Aging 3, 248–257 (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-022-00357-y Accessed September 17, 2024

Attia, Peter, M.D. “Calorie Restriction, Part I: What Does Restricting Calories Have to Do With Longevity?” peterattiamd.com 2018 Mar 12. https://peterattiamd.com/what-does-restricting-calories-have-to-do-with-longevity/ Accessed September 19, 2024

Jarvis, Paul R.E. et al. “Continuous glucose monitoring in a healthy population: understanding the post-prandial glycemic response in individuals without diabetes mellitus”. Metabolism – Clinical and Experimental vol. 146, 155640. https://www.metabolismjournal.com/article/S0026-0495(23)00244-5/fulltext Accessed October 7, 2024

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “The nutrition facts label: What’s in it for you?” fda.gov 2024 Mar 5. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/nutrition-facts-label Accessed October 9, 2024

Cai X, Zhang Y, Li M, Wu J H, Mai L, Li J et al. “Association between prediabetes and risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: updated meta-analysis” The BMJ 2020; 370 :m2297 https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m2297 Accessed March 21, 2025

Change Log